Listen to Morris read these excerpts

Always stay hopeful.

That’s my motto.

You’re probably thinking, he’s such a dreamer, that Wassim. What’s he got to be hopeful about? He’s ten years old and look at his life.

Thanks, but it’s not so bad.

I’ve got a lot to be hopeful about.

So has Uncle Otto.

I can’t wait to tell him what I’ve just discovered at the public library. How it’s going to make such a difference to our lives.

Mine and Uncle Otto’s.

No more Iron Weasels threatening to hurt him if he can’t get the parts to fix their cars. Or if he tells anyone about their crimes. Or if he tries to stop them making monkey noises at me.

Very soon Uncle Otto will be one of the most unthreatened people in Europe.

One of the happiest as well, most likely.

You’re probably thinking, somebody tell Wassim he’s just a kid. Ask him how much hope a kid like him has got of standing up to the Weasels. Has he forgotten they’ve got guns?

No, I haven’t forgotten.

But I’ve still got a lot of hope.

Specially now there’s a person who can help me.

A person who knows more than anyone about staying hopeful and dealing with vicious bullies.

A person called Felix Salinger.

Always be careful in public libraries.

They can be more dangerous than they look.

If you’re lucky there’ll be a librarian who’s kind and helpful. Who says things like, ‘Good morning, Wassim. How’s the research going? Don’t forget to wash your hands before you touch the books.’

But there might also be a senior librarian who gives you long suspicious stares because it’s a week day and you’re not at school.

I’m where I’ve been all week, at a desk behind a shelf of history books and a big panel encouraging old people to use the library’s 3D printer.

I have to be very careful. If the senior librarian sees I’m here again, she might start making phone calls. And the police around here aren’t very friendly to people like me.

It’s worth the risk.

Public library computers are very good at helping you discover people’s secret identities.

People like Felix Salinger.

I’m reading about his very incredible life.

His amazing childhood in Poland in World War Two. How he fooled the Nazis just by changing his name. How the Nazis wanted to kill him very much, but they weren’t able to.

After the way he dealt with all that, I bet Felix Salinger will be able to help me and Uncle Otto with our problems standing on his head.

All I need to do now is find out how to get in touch with him.

I reach for the mouse.

But I don’t click.

I freeze instead.

Behind me, a sound has started. A sound you hear a lot on TV, coming from crowds in football stadiums, specially here in Eastern Europe.

I also hear it up close sometimes. So close I can feel hot breath and blobs of spit on the back of my neck, that’s how worked up the person is who’s making the noises.

The monkey noises.

I jump up and turn round.

Two big teenagers. One still jibbering, the other one grinning. Both wearing Iron Weasels jackets. ‘Whatcha doing, monkey boy?’ says the grinner.

I don’t answer.

What I want to say is, ‘What’s wrong with you lot? Just because you support a football team that’s not much good, don’t take it out on everyone else. Bullying doesn’t make a team better, you idiots.’

But I keep quiet.

Their dads are Iron Weasels too, and if you insult their team, some of the dads get their guns out.

The grinning teenager grabs me round the head. His arm is like a car wrecker’s clamp, twisting my head into his armpit.

I catch sight of what the other one’s doing. He’s stopped making monkey noises and he’s peering at the computer screen.

At the old photos in the newspaper article I was reading about Felix Salinger.

‘Look at that,’ he sniggers. ‘Monkey boy’s doing a school project on Nazis and Jews.’

I lunge towards the desk, trying to turn the computer off.

But I can’t. The grinning Weasel clamps my head even tighter. It feels like it’s being wrenched out of shape.

Doesn’t matter. The article is in English, which I’m pretty sure these two thugs don’t speak because they probably haven’t got mothers who are as smart as mine was.

The other Weasel sees something on the desk and picks it up.

‘William Does His Bit,’ he mutters, staring at the cover of my Richmal Crompton book. ‘Who said you could read about white people, jungle boy?’

‘Put that down,’ I say. ‘It’s not a library book. My grandpa left me that in his will.’

But the Weasel doesn’t put it down. He sees what I’m using as a bookmark.

Grandpa Amon’s secret note to me.

Which is not for anyone else to read.

The Weasel doesn’t care about that. He grabs the note and reads it out loud.

‘Dear Wassim. Your life won’t be easy. And I won’t be there to help you. So if you’re ever in big trouble, see a man called Wilhelm Nowak. He’ll help you because of what I gave him at Speerkopf. Good luck, from Grandpa Amon.’

The Weasels smirk at each other as if this is the funniest thing they’ve ever heard.

‘What did he give him at Speerkopf, wherever that is?’ says the Weasel who’s crushing my head. ‘A kiss?’

The Weasels both chortle.

I can’t stand them being mean about Grandpa Amon, who died when I was three weeks old, but who I love very much.

‘Put that note back,’ I say. ‘I only found it last week and I need it.’

I wish I was like Felix Salinger when he was young. I wish I had the fighting skills he learned from the partisan freedom fighters.

I don’t have any fighting skills, but I’m desperate, so I give one of Felix’s a try.

I twist my body, ignoring the pain, and jab my knee as hard as I can into the back of the headcrusher’s knee.

He yells and half falls and I pull myself out of his grip, staggering backwards and crashing into a bookshelf.

The tall bookshelf begins to wobble.

It starts to fall.

I try to steady it.

Then I see both Weasels coming at me, faces pink with fury.

I let go of the shelves and jump sideways.

The bookshelf falls forward until it crashes against another bookshelf, which stops it.

But the history books don’t stop. They hurtle off the shelves and smack hard into the Weasels, knocking them both off their feet.

Close by, a woman shouts something.

I grab my book and my note.

‘You boys,’ says the woman’s voice, stern and furious. ‘Leave this library immediately.’

The Weasels are both scrambling up, frantically brushing the books away as if they’re poisonous.

The senior librarian is glaring at us. Next to her is the nice librarian, hands over her mouth with concern. The senior librarian holds up her phone. Which I think is official librarian language for do what I say or I’ll call the police.

‘Out,’ she yells. ‘Now.’

I do what she says. I duck past the Weasels and sprint towards the door and outside and across the carpark away from the library.

But not away from the Weasels.

I can hear them behind me, feet clumping, breath sucking.

Getting closer.

‘Maybe the monkey boy’s Jewish,’ one of them pants loudly, like he wants me to hear it. ‘Can you be black and Jewish?’

‘Dunno,’ says the other one. ‘Get his willy out, that’ll tell us.’

They’re even closer.

I have to do something.

Suddenly I stop. And turn. And glare at them.

For a second I haven’t got a clue what I’m doing. The Weasels don’t either. They stop too, a bit startled, but still angry and violent.

I don’t care. I’m bursting with the feelings I get when the Weasels, the grownup ones, bully Uncle Otto. And mock him for looking after me.

‘Change of plan,’ I yell at the teenage Weasels in front of me. ‘Things are different now.’

They stare at me.

‘Your bullying days are over, Weasels,’ I say. ‘We’ve got Felix Salinger on our side now. He eats scum like you for breakfast.’

I glare at them.

They sneer at me, but I can see they’re a bit uncertain. And puzzled. They probably haven’t got a clue who Felix Salinger is.

Tough.

I’m not telling them anything else. Let them find out that Felix Salinger is the same person as the Wilhelm Nowak in Grandpa Amon’s secret message. If they can. I’m keeping Felix Salinger’s details to myself for now. That’s what you do with secret weapons.

‘He must be one tough dude, this Felix Salinger,’ growls one of the Weasels. ‘Which he’ll need to be.’

I know he will.

‘Speerkopf,’ says the other one. ‘We’ll check it out. See who this Felix Salinger is. Decide if we need to be scared.’

‘Or,’ says the first Weasel, ‘if you do.’

They turn and walk away, both of them making loud monkey noises.

I walk in the other direction. Trying to swagger. But not finding it easy. My legs are trembling, and I’m starting to feel uncertain myself now.

I think I might have exaggerated about what Felix Salinger eats for breakfast.

He might prefer muesli.

I’m thinking he probably does, now I’ve just finished a slightly worrying calculation.

When Grandpa Amon met Wilhelm Nowak, who was actually Felix Salinger, at the Speerkopf Regional Nazi Command Centre in Poland in 1942, Felix Salinger was my age.

Which means that now he’s eighty-seven.

Always hopeful.

That’s how I used to be.

Jumble still is.

Look at him. Whatever it was he just heard has made him hysterical with hope. Barking, wheezing, skittering across the kitchen mat, jamming his nose under the back door, rear end a blur.

If he’s not careful, he’ll need an anterior cruciate tail reconstruction.

‘Jumble, please,’ I say. ‘Calm down. Have some breakfast. There’s nobody out there to play with. It’s four-thirty in the morning.’

Jumble gives me an indignant frown.

Speak for yourself, his look says. I know we’re both old and one of us suffers from a leg-related sleeping disorder, but we can still be hopeful. Get a life, Felix.

I smile. But only for a moment.

Another noise outside.

One I hear this time. A plant pot breaking.

Somebody in the backyard.

Jumble is barking again. I ask him to shush so I can listen. He gives my hand a nervous lick. He’s having second thoughts about horizonexpanding social opportunities.

Whoever’s out there has gone silent.

I stand up and creep over to the window, trying to keep the snap, crackle and pop in my knees as quiet as possible.

I give my glasses a wipe and peek out.

Just shadowy bushes. Moonlight on the lawn. And a backpack I don’t think I’ve ever seen before, hanging from the half-open door of the shed.

A door that shouldn’t be open at all.

I remember something I read recently. About desperate homeless people sleeping in Melbourne backyard sheds. At least it’s not cold this time of year. But they’d still be needing a hot meal.

I go to the kitchen bench and switch on the sandwich toaster, just in case.

Then I hear Zel’s voice.

Granddaughters can do that when you haven’t got used to them being gone. Even when they’re thousands of kilometres away, scrubbing up in Syria, hard at work with their parents. They can send a telepathic message whenever they feel like it. Saying things like, Felix, please. Don’t push your luck. It could be a cannibal zombie psychopath out there. Call the police.

I sigh.

Nearly three days and I’m missing her more, not less. I’m missing the amused look she’d have on her face right now. After I told her that cannibal zombie psychopaths probably like toasted cheese sandwiches even more than human flesh.

Zel would argue about that, of course.

I’m going to miss our arguments so much. Nothing makes you feel more hopeful about the future than watching a young person, eyes lit up, out-thinking an old one.

Even when the old one’s you.

A violent noise shatters my thoughts. Somebody thumping hard and loud, over and over, on the back door.

Jumble makes a hurried retreat under the table, scowling and barking.

‘It’s OK,’ I say to him gently. ‘If it’s a zombie I’ll call the police.’

The thumping continues, getting even louder, and a voice calls out.

I blink with surprise.

Did I hear what I thought I just heard?

Hard to know for sure with so much thumping and barking going on.

I tell Jumble to shush and he switches to a loud wheeze.

The thumping stops.

The voice calls out again, yelling my name again, high-pitched and urgent.

I don’t recognise the voice.

But I did hear right the first time.

It’s not a desperate hungry homeless person out there, or a cannibal zombie psychopath.

It’s a child.

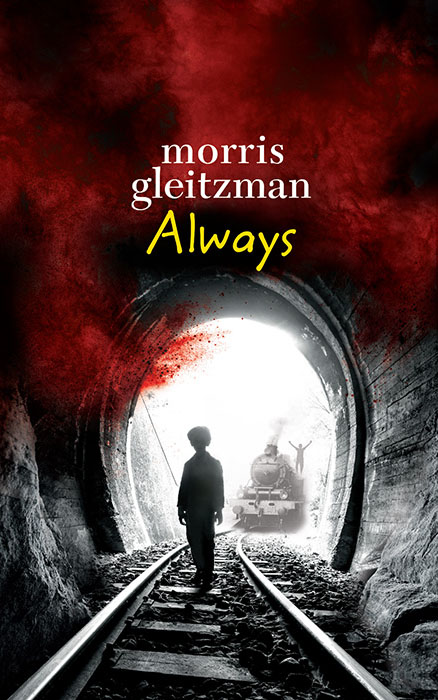

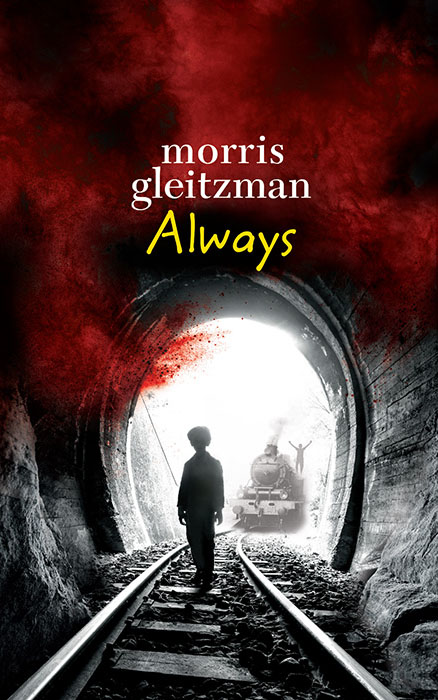

Always is available in bookshops and libraries in Australia, New Zealand and the UK, and online. Buy it here:

Always is available in bookshops and libraries in Australia, New Zealand and the UK, and online. Buy it here:

The audio track on this page is an excerpt from the Bolinda Audiobook Always, read by Morris Gleitzman.

The audio track on this page is an excerpt from the Bolinda Audiobook Always, read by Morris Gleitzman.

Buy it on CD from Bolinda:

… or download as an audio file. Just search for Morris Gleitzman on Audible or the iTunes Store.