Listen to Morris read this story

Great Great Great

Every Thursday afternoon, while I’m sitting here with Mum, I think about my dead rellies.

I call them my great great greats.

You know, like in great great great grandad or great great great grandma or great great great dog etc. Except most of my dead rellies need heaps more greats than that, cause most of them lived bulk amounts of time ago.

As Dad always says, life is short.

So make the most of it.

Which is why, as I’m sitting here waiting, I like to pretend I am them, my greats.

Which isn’t as crazy as it sounds. We’ve all got bits of our greats inside us. We’re actually made of them, inheritancely speaking. Ask your teacher, if you don’t believe me. Or a rellie if you’ve got one who’s still alive and very old, like over fifty.

Today I’m being my great great great etc Uncle Thyroid. Who was a fearless sloth hunter on the icy slopes of the tundra an incredibly long time ago when they hadn’t even invented ski lifts.

The truth is I’m not completely sure his name was Uncle Thyroid.

So I’m partly guessing.

But one thing I do know, which is why I like pretending to be him, he was mega brave.

Gee, it’s cold here on this icy tundra that in only a few thousand years will be known as the BP petrol station on the A12 near Colchester.

It is I, Thyroid The Brave, following the tracks of a giant sloth.

I’m doing it because I’m desperate to feed my family, who are shivering in a cave near what one day will be called the Clacton-On-Sea turnoff.

Oops, information update.

When I say I’m following the tracks of a giant sloth, it’s really just one single track, but a very wide one.

Giant sloths always drag their tummies along the ground when they flee, they can’t help it, which makes them much easier to hunt than say, giant stick insects.

Trouble is, this giant sloth’s gone high up an icy slope. And I’m having trouble following because of how my hunting boots, which I carved out of ice, keep slipping on all the other ice.

I wish there was a way of getting up there that didn’t involve slithering on my tummy.

I know. I’ll find myself a walking stick.

Here’s a pile of old branches and twigs, must be something here.

Yes, that looks like a good one. Sturdy and stout, perfect for a fearless sloth hunter.

I’ll just reach in and drag it out ...

Oh no, what’s tickling my arm?

Please, don’t let it be what I think it is.

Let it be a liver-eating tundra wolf instead. I’m nowhere near as scared of those as I am of ...

Oh no, I don’t think this is a wolf up my sleeve. My hunting jerkin isn’t that loose. And liver-eating tundra wolves don’t tickle like this.

I shake my arm. I see what’s crawling out of my sleeve. I scream.

‘Aaaaaaaarrrrrrgh, a spider!’

I run.

Down the slope.

Sliding, howling, desperate to get away.

This is an outrage. There’s not a single handrail anywhere around here.

My feet slip and I hurtle down the icy slope on my tummy, straight towards the glacier below. With its deep dark ice chasms.

Which, legend says, are bottomless.

Except, I think as I hurtle into one, that can’t be right. There’s got to be some sort of bottom down there eventually.

And a bottom would have a pile of snow on it, probably, just waiting to break my fall.

Deep, soft, fluffy snow.

Full of frozen spiders.

‘Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaarrrrrrgh.’

The good thing about being a great great great in your imagination is you don’t have to hang around for funerals etc.

You can check with Mum that it’s still not our turn yet, then sit back and move on to the eleventh century, where I am now.

It’s lovely weather in France at this time of year.

These big blocks of stone that I’m clinging to as I climb up this castle wall are really warm from the afternoon sun. They’re so pleasant to the touch, I’d hate to be shot through the head with an arrow and not be able to enjoy them any more.

So far, so good.

And here’s a window ledge to help me up.

Oh dear. This isn’t so good.

A young woman inside the room has spotted

me. She’s getting up from her spinning wheel and coming over to the window.

She’s about my age, and she actually looks quite friendly. Maybe she doesn’t get out much with other young people and so she’s a bit lonely. Just a guess, from the way she’s not pouring boiling oil on me.

‘Bonjour, interesting stranger,’ she says. ‘Who are you?’

‘Gaston at your service, mademoiselle,’ I say, with a flourish of my helmet, which is a bit difficult with both of my hands hanging onto the window ledge, so I have to ask her to flourish it for me. ‘Junior soldier, second class.’

‘Nice to meet you, Gaston,’ she says.

We smile at each other.

I’m too embarrassed to say that my boss is the Countess of Orleans, who has commanded me to slip into this castle unnoticed and open the drawbridge from the inside so she and her army can seize the castle for herself on account of her other castle needing re-grouting.

‘Gaston,’ says the young woman. ‘Can I share a secret with you?’

I nod, feeling a bit guilty that I haven’t shared mine with her.

‘Can you help me get out of here?’ she says. ‘My mother has kept me prisoner in this tiny room for three years because she’s jealous of my beauty. Plus she wants my bedroom to age cheese in.’

Her face is so hopeful, how can I say no?

‘OK,’ I say. ‘I’ll give it a try.’

The young woman grabs her spinning wheel,

and a big bulging brand-new travel bag as well, and clambers onto my back.

Slowly I climb down the castle wall.

‘I’m Lucienne,’ she says on the way down. ‘This is very good of you, Gaston.’

‘My pleasure,’ I say. ‘I like climbing.’

‘You’re very good at it,’ says Lucienne.

‘It’s a family thing,’ I say. ‘We’ve got this legend about one of our ancient ancestors who climbed out of a bottomless chasm in a glacier using only his hands and a walking stick woven from facial hair.’

‘Incroyable,’ says Lucienne.

‘He was being chased by a spider,’ I say.

We reach the bottom of the wall.

‘Merci,’ says Lucienne. ‘I’m very grateful. But also very curieuse. Your ancestor did not like spiders?’

‘Not really,’ I mumble.

‘It takes all sorts,’ says Lucienne with a shrug.

‘Merci again, Gaston. How can I repay you? The least I can do is buy you a slap-up feed. I’ve got lots of gold saved up from my pocket money, and I’ve heard that the inn near here does cream buns and really delicious pig-gut sausages.’

‘Yum,’ I say. ‘Thanks. I’d love that.’

Then my insides droop.

‘But I can’t,’ I say. ‘I have to finish my mission.’

Lucienne frowns, and I can see she’s wondering what it is I’m actually doing here.

I hesitate.

But not for long. Mum has often told me about the two things that are very vital for a close and trusting relationship.

Honesty and regular visits.

‘The thing is,’ I say, hating to have to say it, ‘my mission involves your castle being violently seized and totally redecorated.’

Lucienne shrugs again.

‘Pas de probleme,’ she says. ‘I’m never coming back here anyway.’

Oh well, I think to myself. At least this is what will one day be called a win-win situation.

For Lucienne and for the Countess.

But not for me, sadly. I think Lucienne and I could have been friends. If only I hadn’t sworn on my honour to the Countess to do everything in my power to get her into the castle. Which was the least I could do after she touched me on the shoulder with her sword. And flicked that spider off.

‘Au revoir,’ I say to Lucienne. ‘And good luck. It’s been very nice meeting you. Very, very nice.’

‘Don’t be a dopey duck,’ she says. ‘I’ll wait.’

Climbing up the castle is easier the second time, because now I’ve got delicious food to look forward to, and a new friend.

But we must be careful on our way to the inn.

We must make sure we avoid the local market. The Countess and her army are there buying sheets and pillowslips for the castle.

Ah, here’s the window ledge again.

That was quick.

I reach up and grab it.

And freeze in horror.

Because of what’s crawling all over the ledge. And now, all over my hands, and arms, and into my ears.

Spiders.

Frantically I try to ignore the sickening fear that has cursed my family.

I force myself to climb on, past this nightmare. But the tickling is just too tickly. And revoltingly spidery.

My hands slip off the ledge.

I plummet down.

Towards the hundreds of spears in the mud of the moat, razor sharp metal tips pointing upwards just below the surface of the water.

I was able to squeeze between them earlier, but now, no chance.

‘Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaarrrrrrgh.’

Huh?

I’m not getting stabbed. Not hundreds of times, not even once. I’m just bouncing up and down on something stretchy and a bit sticky.

‘Thank goodness,’ says Lucienne’s voice.

And, as she said earlier, incroyable.

I’m lying on long thick strands of sticky rope, stretched across the moat. With pieces of Lucienne’s spinning wheel anchoring them at each end.

Lucienne grabs my hand and helps me down.

‘I’ve been spinning that for three years,’ she says. ‘Hoping that one day, when it was long enough, it would be a ladder for me to climb down. But I’m so glad it did the job of saving your life.’

So am I, even though I do have sticky strands of something all over my clothes.

‘Thank you, Lucienne,’ I say. ‘I’m speechless.’

‘You’ll think of something else to say, Gaston,’ says Lucienne. ‘Once you’ve had a cream bun. Just relax while I pop over and open the drawbridge for the Countess. It opens from the outside if you kick the bottom left hand corner.’

While she’s gone, I suddenly do think of something else to say.

‘Lucienne,’ I ask when she gets back. ‘Just now you mentioned about spinning that sticky rope. What was the stuff you actually spun it from?’

Lucienne grins.

‘Spiders webs,’ she says.

She grabs my hand and we hurry away from the castle.

I look back over my shoulder, squinting up at the window ledge that is still alive with not quite so terrifying furry wriggly creatures.

‘Thank you,’ I whisper to them.

Another good thing about being a great great great in your imagination that is you don’t have to hang around for gooey romantic stuff and weddings etc.

You can pop into the nineteenth century and find yourself opening a window of a luxurious fourth floor apartment in Constantinople.

From the outside.

So, you think excitedly to yourself, as you step inside and untie the rope from round your waist, the Queen of the Cat Burglars strikes again.

Actually, I don’t know why I’m saying you. Not to sound mean, but this is my great great great grandmother that I’m being.

OK, I’m not sure about the Queen of the Cat Burglars bit, but you have to use your imagination with history, specially when you’re imagining yourself doing stuff in it.

I creep across the grand living room, careful not to tread on any empty take-away food containers, which in a place like this would be made of very noisy gold and porcelain.

I’m here for jewels.

Fabulous, priceless diamonds and emeralds.

And any books that look interesting.

The bookshelves in front of me are vast. Floor to ceiling, wall to wall. Full of books. And not boring out-of-date encyclopedias and ancient coffee-table books about interior decorating in medieval castles.

Stories.

I can tell they’re stories from the fingerprints gleaming in the moonlight on the leather covers. Only stories can make you so excited or weepy or wetting yourself with laughter that you leave part of yourself on the book.

I grab an armful of books.

Forget diamonds and emeralds.

Who wants to be lugging less important stuff

when you’ve got a pile of good books to keep safe on a four-storey climb down a brick wall?

I turn to head back to the window.

Except I don’t.

Because I spot something in front of me, in a corner of the bookshelf section I’ve just emptied.

A small spider.

Which is slowly and patiently weaving a big beautiful complicated web that gleams like silver in the moonlight.

Which is exactly what I’ve always wanted to do.

Not be a spider, don’t be dopey, my family has very mixed feelings about spiders.

I mean, to create something that is incredibly exquisitely eye-wateringly beautiful. Plus useful in a practical way.

I think that’s why I steal things.

Things that are beautiful and useful both at the same time. Really nice kitchen appliances, for example, studded with diamonds and emeralds.

And why I also steal books.

Because it’s stories that remind us anything is possible. Even a Queen of the Cat Burglars giving up her life of crime. And stealing – oops – buying herself some tools, and a book about how to make beautiful and useful things, with large numbers of easy-to-follow diagrams.

And getting started.

‘Thank you,’ I whisper to the spider.

Which gives me a weird feeling. Like part of me has done this before.

I turn to leave. Except again I don’t.

I find a piece of paper in my pocket, and a pen studded with diamonds and emeralds.

It’s from a mansion in Thessaloniki I spent a few minutes in last week. With it I write a note to the owners of this apartment.

A short note saying I’m taking the books, but I will return them after I’ve read them, a process that in a few more years will be known as going to the library.

Also, I write, ‘Be kind to the spider, OK?’

The best thing about being a great great great in your imagination is you can come back to the here and now the moment you need to.

The moment a prison guard finally comes into the visitors’ waiting room and says to you and Mum that you can both go in now and see Dad.

‘Thanks, officer,’ says Mum.

She always says that.

I don’t say anything this time. I don’t want to be attracting attention to myself.

Specially not to what’s in my pocket.

The matchbox.

And what’s in the matchbox.

I haven’t asked, but I’m pretty sure you’re not allowed to bring spiders into jails.

This one’s really good at spinning webs.

I watched it for ages yesterday in our shed. And decided it was the spider for me. I mean for Dad.

When you’ve been sentenced to a year in prison for stealing freezers, and you’re sharing a cell with someone who snores every night, you can end up spending most of your time wishing you could get out and steal some earplugs.

And I don’t want Dad to steal any more.

So I’m hoping he’ll spend his nights watching the spider instead. And start to get interested in other possibilities for a new career. Such as doing something slowly and patiently and beautifully.

Since Dad came in here, he’s always saying how really great it is to have his family behind him. He means me and Mum, and we are.

But in a minute, when I give Dad the spider, I’ll explain to him how actually his whole family is behind him.

All of them.

And I hope he’ll think that’s really really great.

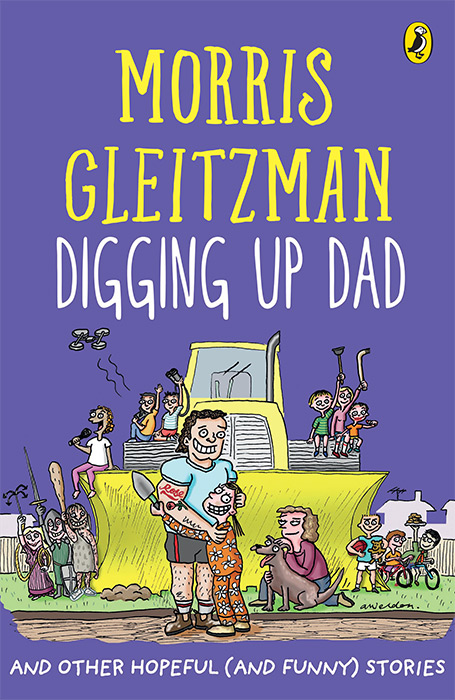

Digging Up Dad is available now in bookshops and libraries in Australia and New Zealand, in the UK soon, and online. Buy it here:

Digging Up Dad is available now in bookshops and libraries in Australia and New Zealand, in the UK soon, and online. Buy it here:

The audio track on this page is an excerpt from the Bolinda Audiobook Digging Up Dad, read by Morris Gleitzman.

The audio track on this page is an excerpt from the Bolinda Audiobook Digging Up Dad, read by Morris Gleitzman.

Buy it on CD from Bolinda, or from Amazon in the USA:

… or download as an audio file. Just search for Morris Gleitzman on Audible or the iTunes Store.