Listen to Chapter 1

Chapter 1

I should be arrested for this.

The time is approximately 4.17 p.m. and I’m proceeding in an easterly direction along a corridor in one of Australia’s most seriously top-notch boarding schools.

‘Look at this floor,’ says Mum. ‘Genuine marble.’

‘These wall panels are oak,’ says Dad. ‘Real wood.’

‘Solid brass chandeliers,’ says Uncle Grub, his leather jacket creaking as he gazes upwards. ‘Pity I didn’t bring the van.’

I know I should be thrilled like they are.

I wish I was.

But instead I just feel anxious.

We walk past huge sideboards with genuine priceless porcelain vases on them. We stare up at genuine oil paintings of famous historical people who went to this school.

‘That’ll be you, Bridget,’ says Dad, pointing up at a dead Prime Minister.

I know I should be grateful. Mum and Dad have worked incredibly hard to send me to this school.

I should feel lucky and privileged, like the headmaster said just now when he was showing us around.

It’s a crime not to.

But I don’t feel grateful, I feel close to panic.

I’m terrified Uncle Grub’s going to nick one of the vases.

I glance up and down the corridor. No security cameras. No infra-red burglar alarms. There’s a photocopier over there that’s not even chained to the wall. This place is just asking for it.

Uncle Grub is stroking a vase.

‘Awesome crockery,’ he says.

‘George,’ murmurs Mum. ‘Behave.’

I know what she’s saying. She’s warning Uncle Grub that if he fingers anything and gets sprung and we end up in a high speed police chase across the school grounds and my education suffers, she’ll do him.

‘Little suggestion, Grub,’ says Dad. ‘If you go and warm the car up for us, you won’t be tempted, eh?’

‘I was only looking,’ mutters Uncle Grub.

The expression on Dad’s face doesn’t change. Dad might be a criminal, but he doesn’t believe in stealing.

Now Mum and Dad are on the case I feel a bit better. I take a deep breath and try to calm down. It’s a stressful experience, being sent to boarding school.

Uncle Grub gives me a kiss on the head.

‘Study hard, gorgeous,’ he says. ‘Show those posh mongrels what you’re made of.’

He strolls off towards the carpark.

‘Thanks, Uncle Grub,’ I say.

No need to panic.

Not yet.

‘Wish I’d gone to a school like this,’ says Dad. ‘Be a different person if I had.’

Mum kisses him on the cheek. She looks really pretty in her new frock, specially with her hair in ringlets and the sleeves covering her tattoos.

‘I love you just the way you are,’ she says to Dad as we step outside into the sunshine. She means it too, even though Dad’s wearing a yellow shirt with a blue suit.

Dad grabs Mum on the bottom and they both laugh.

I look anxiously around the school grounds. Other kids and their parents are strolling about, mostly wearing tennis clothes with sweaters knotted over their shoulders.

None of them are looking at us.

Not yet.

I peer over towards the carpark, trying to see if Uncle Grub is getting into our car or someone else’s.

‘Check this,’ says Dad proudly, patting the wall of an old building. ‘Genuine sandstone.’

Suddenly I can’t keep quiet any longer. I hate being a squealer, specially on my first day, but I can’t stop myself.

‘I don’t want to go to this school,’ I say quietly.

Mum and Dad stare at me, shocked. Then Mum gives me a hug.

‘I know, love,’ she says. ‘It’s all new and scary. But you’ll feel different when you’ve made some friends.’

I sigh.

Friends?

Me?

Dream on.

Dad puts his arm round me too. ‘By the time we see you at parents’ night tomorrow you’ll be loving it here,’ he says. ‘Trust me.’

‘This school,’ says Mum, ‘is going to give you everything me and Dad didn’t have.’

I nod sadly.

I can’t do it to them. They spent months choosing this place. Mum cancelled the plastic surgery on her tattoos so they could afford the fees. How can I tell them I’d rather be going into Mrs Posnick’s class at my old school?

‘You’ve got to admit,’ says Mum, giving me another squeeze, ‘this place is better than your old school.’

I nod again.

But I don’t mean it.

My old school’s only ten minutes from home by foot. The uniform’s a comfortable t-shirt instead of this scratchy blazer. And the teachers and kids are fantastic. Nobody tries to push you into being their friend. If you want to keep to yourself so nobody finds out your family are criminals, you can.

This school is crawling with the kids of lawyers and judges and commissioners of police. If they find out what Mum and Dad do, we’re sunk.

I open my mouth to tell Mum and Dad that sending me here is putting our whole family at risk and that they’re making a terrible mistake.

But I don’t.

Their faces are so hopeful.

I remember how miserable they were when Gavin got put away for shoplifting. I’m their only other kid. I can’t hurt them too. I have to try and get through the next seven years.

Somehow.

For them.

As I’m thinking this, Dad steers me over to a complete stranger.

‘S’cuse me,’ says Dad, blocking the stranger’s path. ‘I’m Len White. You a teacher?’

The stranger, a tall skinny bloke with a beaky face and a bundle of folders under his arm, looks at me and Mum and Dad about twice each.

‘Creely,’ he says. ‘Science and Personal Development.’

Dad pumps Mr Creely’s hand. Mr Creely gives him a thin smile.

‘This is my daughter Bridget,’ says Dad. ‘She’s just starting in year six. Bridget’s a very sensitive and top-notch young person. If you could see your way clear to helping her settle in, I would be personally very grateful.’

Mr Creely gives me the thin smile.

‘We regard every student as sensitive and er, top-notch,’ he says. ‘Every one of them will receive the very best care and support. As young Bridget will discover at her first assembly tomorrow morning.’

Dad reaches into his inside pocket.

With a jolt of panic I realise what he’s going to do.

No, Dad, I plead silently. Not here.

It’s too late.

Dad pulls a plastic object out of his pocket and presses it into Mr Creely’s hand.

‘Bulgarian gameboy,’ says Dad. ‘Seriously top-notch quality. With my compliments.’

Mr Creely stares at the gameboy, horrified.

‘Thank you,’ he says. ‘But I couldn’t possibly ...’

‘Don’t fret,’ says Dad. ‘I’ve got a warehouse full of ‘em. Keep a friendly eye on Bridget for me and I’ll sling you an Iraqi blender next visit.’

I pray Mr Creely doesn’t ask to see the import documents for the gameboy. I’m not sure if the Bulgarian businessmen Dad deals with can even write.

‘Um, thank you,’ mutters Mr Creely and hurries away.

‘Nice bloke,’ says Dad, ruffling my hair.

Mum is frowning at Dad’s jacket pocket. I can see she’s wondering what else he’s brought along from the warehouse.

‘We should probably be thinking about going, love,’ says Mum to me. ‘Would you like us to take you back to your room and say goodbye there?’

‘No thanks,’ I say. ‘The carpark’s fine.’

I just want to get them out of here before Dad tries to give a set of Algerian hair-curlers to a passing high court judge.

We go over to the car. Mum spends a long time hugging me and saying loving things. Normally I’d be glowing with happiness, but I just can’t concentrate, not while we’re standing next to the only Mercedes in the carpark with dents and a spoiler and flared mudguards. It’s not Dad’s fault. Uncle Grub gave it to him. In our family we believe it’s rude to criticise presents or get them panel-beaten.

Dad says lots of loving things too, and gives me a Turkish personal organiser.

Uncle Grub waves at me through the car window.

Then they drive away.

I wave back, trying to hold the tears in so I won’t draw attention to myself.

I’m sad because they’re going, but I’m even sadder because I know the real reason Mum and Dad are paying a fortune to send me to a boarding school that’s only an hour by car or school bus from our place.

They think if they keep me out of the house I won’t end up like them.

Crims.

Which is hard for me because they’re kind and generous and good and I love them and I do want to end up like them.

They’ve gone.

I’d better get inside before other parents start talking to me.

Hang on, what’s that cloud of dust coming through the school gates? It’s a car going really fast. Spraying gravel onto the flowerbeds. Is it them rushing back so Dad can give me an Israeli calculator?

Oh no.

It’s something even worse and it’s heading straight for me.

A police car.

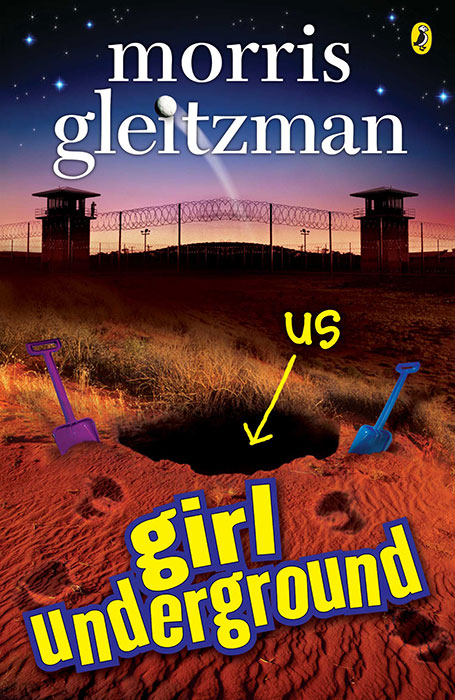

Girl Underground is available in bookshops and libraries in Australia, New Zealand, the UK, and online:

Girl Underground is available in bookshops and libraries in Australia, New Zealand, the UK, and online:

The audio track on this page is an excerpt from the Bolinda Audiobook Girl Underground, read by Mary-Anne Fahey.

The audio track on this page is an excerpt from the Bolinda Audiobook Girl Underground, read by Mary-Anne Fahey.

Buy it on CD from Bolinda (or from Amazon in the USA):

… or download as an audio file. Just search for Morris Gleitzman on Audible or the iTunes Store.