Listen to Morris read the beginning of Tweet

Getting Started ...

Clyde is standing on the table.

His wings are trembling.

If you ask him why they’re doing that, he’ll be happy to tell you.

‘Jig,’ he’ll chirp.

Then he’ll give you a hopeful look, because you’re human, which means you’re one of the smartest creatures on earth. One word, Clyde hopes, is all you need to work out what he’s saying in his mind.

Look at this jigsaw puzzle. We’ve almost finished it. I mean, who wouldn’t be excited? Specially me, because I’m a budgie.

Clyde often hears Jay and Poppa express the view that budgies are the friendliest birds in the whole world. And the best at doing jigsaws.

He loves hearing that.

Poppa and Jay are humans, and there’s nothing humans don’t know. Even young ones like Jay. So if they say you’re good at something, you are.

Thinking about that now makes Clyde glow with pleasure. He doesn’t pause to wonder if his wings might be trembling for another reason.

That they might know something he doesn’t.

That his tiny wing filaments, before they were his, might have been slowly learning something for millions of years in billions of his ancestors. How to be sensitive to more than just passing breezes and almost-finished jigsaws.

And now, for the first time, they’re picking up tiny murmurs from Clyde’s own future.

About what might happen to him.

Tomorrow, and next week.

A huge adventure, for example. And a tragic loss.

And mind-boggling new friends. And, high above a deep and angry ocean, his life hanging by a thread. Lots of threads actually, if you include his wing filaments.

Clyde isn’t thinking about any of that.

He’s looking at Jay and Poppa, and the jigsaw pieces they’re holding.

Yippee, thinks Clyde. We’re nearly there. Jay and Poppa have got the last two pieces of truck tyre, and I’ve got the last wheel nut.

Three more pieces and we’re finished.

Suddenly his feet can’t stay still, and he does a happy little dance on the table.

Poor Clyde.

He doesn’t know yet that he’s nowhere near finished.

1

Clyde stops doing his happy dance.

He’s starting to feel sad, which happens quite a lot these days.

Mostly at times like this. When he’s got the last piece of a jigsaw gripped in his beak. And Jay and Poppa are clicking their last pieces into place. And Clyde remembers how the family used to be. All five of them around the table doing this together.

And now there’s only three.

Clyde does a sad half-chirp, half-sigh.

‘Righty ho,’ says Poppa, looking at Clyde with a sympathetic smile. ‘What we need now is a budgie to finish the job.’

These days, Poppa says this as they get to the end of each jigsaw. Clyde knows why. It’s to cheer him up. Which it usually does.

Sometimes a bit too much. Sometimes Clyde gets too excited and does a poo on the table.

Even when he does, Poppa and Jay are amazing. Wiping it up and saying kind and gentle things and never getting cross. Which, Clyde thinks, is incredible considering everything else they have to deal with these days.

‘Here’s a budgie,’ says Jay. ‘Here’s one who can finish the job.’

He grins at Clyde.

‘Job,’ chirps Clyde through a beakful of jigsaw wheel nut.

I’m so lucky, he thinks, having a family like this. So good at cheering you up. Even when their own hearts are so worried and sad.

Clyde wishes he could thank Jay and Poppa for everything. Out loud, so they wouldn’t have to guess any of the details.

Will I ever be able to do that? he wonders. Chirp all the human words? Maybe, if I do more practice and beak exercises. And, if necessary, plunge into the dark depths of an angry ocean.

Clyde stops, puzzled.

Angry ocean? he thinks. Where did that come from?

He sees that Poppa and Jay are both waiting, smiling and patient, for him to finish the job.

But before Clyde can hop onto the jigsaw and click the last piece into place, loud thumps come from the front door of the flat.

Clyde spits out the wheel nut. You have to when there are more important things happening.

On the other side of the table, Jay is scrambling off his chair.

Clyde feels a stab of concern.

Look at him, poor kid.

Everything he’s been through lately, all that disappointment, and his dear freckly face is still hopeful.

While Jay hurries over to the front door, Clyde crosses some feathers and makes a wish.

Please, he chirps silently. When Jay opens the door, please let it be Mum and Dad.

Poppa is giving a wheezy sigh.

‘Sorry, matey,’ he says to Clyde, with his usual apologetic nod up towards the ceiling. ‘Best play it cautious.’

Clyde doesn’t need to be told. He’d be the first to admit that his knowledge of property law is sketchy. But one thing he does know is that in these flats, only pets with four legs are allowed. Which means no spiders, no slugs, no sharks and no birds.

‘OK, matey,’ Clyde says to Poppa.

Clyde flies up as usual to the lightshade hanging from the ceiling, drops down inside it and perches out of sight on the switched-off bulb.

From below comes the sound of Jay opening the front door.

Clyde grips the bulb with his feet and hangs upside down so he can peek out.

Jay’s shoulders are sagging.

Clyde sees why.

It wasn’t Mum and Dad who were thumping on the door.

It’s the postie. She hands Jay a letter with a smile and calls g’day to Poppa. Who waves and thanks her for bringing the letter upstairs.

Jay closes the door and brings the letter over.

Poppa looks at the envelope, his face hopeful. Then his shoulders sag too, and he tosses it onto the table without opening it.

‘Sorry it’s not from the government,’ says Jay. ‘I think they’re really slack.’

‘Thanks, matey,’ says Poppa.

They give each other a hug, and start talking in quiet, sad voices.

Clyde isn’t totally sure what a government is, but he’s pretty sure that when humans came up with the idea, they would definitely have wanted it to help people.

Which should definitely include, Clyde reckons, a family whose Mum and Dad haven’t come home from a trip to Africa.

Poor Poppa and Jay, he thinks.

Clyde grabs a beakful of the bulb-toasted biscuit crumbs he keeps in the creases of the lightshade for just these occasions. He flies down and offers some to Jay and Poppa, to cheer them up.

‘Sorry, matey,’ says Poppa, stroking Clyde’s head. ‘Not really in the mood for chewing.’

‘I’ll just have one, thanks,’ says Jay.

He puts Clyde onto his shoulder, takes a crumb and eats it.

‘You have the rest,’ says Jay.

Clyde understands.

That’s what worry and sadness does. Ruins your appetite. Even for delicious treats from a family member’s beak.

Poppa is wheezing as he gets up from his chair.

Jay gently puts Clyde on the table and helps Poppa.

Clyde wishes he could help too. All this sadness and stress must be putting a strain on Poppa’s breathing. But unlike Jay, Poppa isn’t a big fan of loving pecks on the ear.

‘Come on, Poppa,’ Jay is saying gently. ‘You’ll feel better after a snooze.’

‘Yes, doctor,’ says Poppa with a wink to Clyde.

Jay takes Poppa’s arm as they walk slowly past Mum and Dad’s room and into Poppa’s room.

Clyde is feeling weary too, specially in his neck. It’s never easy, getting toasted biscuit crumbs down your throat when you’re feeling this emotional.

But he waits for Jay to come back out, in case Jay needs a quick loving peck on the ear.

Poor kid. This is the first school break since Mum and Dad disappeared. All Jay’s friends are on holiday with their parents. Which must be making Jay feel even more unhappy.

Clyde wonders hopefully if a couple of new jigsaws would help Jay. With sandy beaches on them and suitcases and lots of rain.

Jay doesn’t come out.

Probably waiting for Poppa to fall asleep, thinks Clyde. Which’ll probably take ages now that a leaf blower has started howling next door.

Clyde flies into the kitchen and up to his shelf.

He squeezes past Mum and Dad’s globe of the world, which Poppa put in front of his cage to hide it in case the building manager pops in unexpectedly to count Clyde’s legs.

Then he wriggles under the cloth that Jay put over the cage so the kitchen light won’t wake him up if anyone needs a late night cup of tea.

Humans, thinks Clyde. Not just kind, also very creative with practical problems. I’m so lucky that I’m learning to be one myself.

Clyde steps into his cage and pulls the door shut behind him. After his eyes get used to the cosy gloom, he hops up his ladder and onto his swing.

Ahhh, bliss.

Except for the leaf blower, still roaring outside.

Chirping shell grit, thinks Clyde wearily. We’re a worried family here, trying to stay hopeful. Can’t you please, just for once, stop that chirping racket?

To his surprise, the leaf blower stops.

But the noise doesn’t.

A gruff human voice starts shouting angrily. ‘Get lost, you mongrels,’ yells the voice, which sounds to Clyde like a neighbour. ‘I’m trying to shift these leaves. Rack off or I’ll mulch the lot of you.’

Clyde is shocked.

Yes, humans can be a bit grumpy sometimes. It’s because they’re always so busy.

But this one has totally forgotten his manners.

After a few more moments, and a few more human swear words, the yelling stops.

Clyde blinks in the sudden silence.

With just the distant sound of Poppa snoring peacefully.

Which is a relief.

Clyde lets the swing rock him gently backwards and forwards, soothing his sore gullet and relaxing his mind.

But only for a moment.

He’s got thinking to do.

About Jay, a boy without his mum and dad.

And about Mum and Dad, who went on a scientific bird trip and got completely lost in that big place halfway up the globe called Africa. The place that’s the same shape as a human ear. Which Poppa says is ironic because Mum and Dad have been gone for a big number of sleeps, and nobody’s heard from them.

And about Poppa, who misses Mum and Dad a lot, specially Mum, who’s his daughter.

And then there’s me, thinks Clyde sadly, who’s worried sick about them all.

So what can we do?

Clyde knows what would be best. A rescue team, going to Africa.

But who? They’d need to be fully trained, and have their own globe of the world. The police? The army? The people who get birds’ nests out of gutters without damaging the gutters or the birds’ nests?

Clyde sighs.

He doesn’t know any of those people, not personally, and he’s pretty sure Jay and Poppa don’t.

Neither do the government, judging by them not answering a single one of Poppa’s begging-for-help letters.

Who else is there? thinks Clyde.

He slumps back against the cage wall. Which makes his mirror start spinning.

When the mirror finally stops, Clyde sees his own reflection staring at him.

He realises what the mirror is trying to say.

Me? says Clyde, stunned. Go to Africa?

But slowly, as the shock fades, the idea of it starts to trickle through his filaments, making his tail feathers tingle with excitement.

OK, there are some practical issues.

‘I’m not fully trained,’ he explains to the mirror. ‘I’m not even fully human. Someone would have to carry my cage.’

The mirror doesn’t seem to think this is a big problem.

‘Plus,’ says Clyde, ‘Africa does make me feel a bit nervous. OK, very nervous.’

Clyde hasn’t ever forgotten the jigsaw of Africa he and Jay and Poppa and Mum and Dad did once.

It was the scariest jigsaw he’d ever seen. And not just because there was so much sky. The wild animals were terrifying, and the wild insects, and the even wilder birds.

‘I wouldn’t be so worried if I was a large tough human,’ Clyde explains to the mirror. ‘Or an eagle with very big claws who could eat the intestines of violent attackers without getting a tummy ache. But I’m not.’

The mirror still doesn’t seem to think this is a problem.

Clyde stares at the mirror for a long time.

Maybe you’re right, he thinks, feeling his wing filaments tingle again.

Crazy, but right.

I wonder if Poppa and Jay would come with me?

2

Jay rolls around restlessly in bed.

It’s 4.15 am, and he’s very tired, but he doesn’t want to go back to sleep.

He wants to give Mum and Dad one more try.

OK, he knows exactly what his friends at school would say.

‘You’ve already tried this, bird-brain. You’ve tried it heaps and it didn’t work. Give yourself a break and find another way to contact your parents.’

Thanks for the advice, thinks Jay. But right now this is the only way I’ve got.

He spends a few moments in the dark thinking about Mum and Dad’s work.

To inspire him to do this right.

Then he tries once again to contact Mum and Dad using only his mind.

Hi, Mum and Dad, he says silently. We’re a bit worried here. You’ve never been four weeks late before, so we’re hoping you’re OK. Please, don’t panic if something not good has happened. Rescue is on its way. Poppa’s onto it. He’s getting the university and the government to do it. They haven’t actually answered any of his emails and letters yet, but I reckon they’re just waiting for more details. Like, where in Central East Africa are you, exactly? Are you hurt? Can you still walk? Is Mum still getting those bad headaches when you snore, Dad?

Jay pauses, listening inside his head for a reply.

He knows Mum and Dad’s voices will probably be very faint. The African birds they’re working with generally hang out in very deep valleys.

He listens some more.

Nothing so far.

Not even very faint.

Jay doesn’t give up.

Mum and Dad never gave up, and look at them. What they discovered. That birds can stay in touch with each other over vast distances. By just using their minds. Without any phones or technology or anything.

Not giving up, thinks Jay, made Mum and Dad two of the best bird scientists in the world, and also really good at coping with things.

He’s been telling himself that ever since Mum and Dad’s last phone call from Africa.

A call he thinks about every day.

‘We’ll be home in a week or so,’ said Mum. ‘We’re working on something very urgent with a friend. It’s very exciting.’

Before Jay could ask her what it was, the phone signal dropped out, which Jay knows does happen sometimes in Africa.

But they weren’t home in a week.

Or even two.

Poppa called them about twenty times. With no answer. Jay could see how worried he was.

Jay tried to stay positive, reminding Poppa that buses in Africa are sometimes very late.

‘Not that late,’ said Poppa quietly.

‘Maybe they found some injured birds,’ said Jay. ‘And used most of their clothes as bandages, so they can’t leave till the birds are better.’

Jay wanted to believe this, but something was nagging in his mind. Making it very hard to stay positive.

When Mum and Dad are on a trip, they call every day. Their satellite phone works everywhere.

So something bad must have happened. To their phone, or to their solar charger. Or to their friend, or to them.

That’s when Jay asked Poppa if he thought it was possible for humans to do what birds can do.

Make contact long-distance without phones or postcards or emails or TikTok or anything.

Poppa thought about that.

He gave Jay a long encouraging squeeze.

‘If you don’t try,’ he said, ‘you’ll never know. And don’t forget, as I think Qantas once said, love can travel any distance. Or was that Shakespeare?’

Every night since then, Jay has tried to make his love travel all the way to Mum and Dad.

Wherever they are.

And he hasn’t given up, specially not now.

Because tonight he’s got something amazing to tell them. And he knows that when Mum and Dad hear it, they’ll be gobsmacked.

Today, he says to them in his mind, you’ll never guess what happened. Poppa was trying to have a snooze. Someone was using a leaf blower down in the street. There was yelling, so I looked out the window. And I couldn’t believe what I saw.

Jay pauses.

Will Mum and Dad believe it?

He remembers the bird-watching holidays they all had together when he was little. There was one holiday rule they never broke. Two, if you include that every breakfast must have ice-cream.

But the main rule was, never exaggerate about the birds you see.

And Mum and Dad know I would never do that, thinks Jay.

The leafblower man, he says silently to them, was surrounded by birds. Standing everywhere. Getting in his way. I did a count like you taught me. More than two hundred birds. The man was yelling and blowing air at them, but they just stayed there. So he gave up and drove off, and then the birds left as well.

Jay pauses again.

Now for the really unbelievable part.

There’s something even more amazing, he says. The birds weren’t just from one flock. They were all different. Redcapped plovers and ganggang cockatoos and forest ravens and heaps more. All different.

Jay stops. He’s breathless with amazement just saying it. He knows he doesn’t have to say more.

Mum and Dad will be breathless too. Totally and completely. Mouths flopped open even if they’re in the middle of an African dust storm.

Because everyone knows, if they’re a bird expert, that none of those birds would ever do that. Never hang out with those other birds. Never even risk being that close. Not ever. Not in the whole history of the world.

Jay waits to hear the faint sounds of Mum and Dad being amazed.

Nothing.

He waits some more.

Still nothing.

The familiar sick feeling of disappointment burns inside him.

Mum and Dad still can’t hear him. This still isn’t working. He still doesn’t know what’s happened to them. Why they’re still not home, all these weeks after they should have been. Why they haven’t even been in touch.

Jay takes some deep breaths.

He sits up in bed.

OK, he says to himself. You did your best. You busted your guts. And it hasn’t worked.

So accept it.

Birds can do mind messages, humans can’t.

Jay sighs. Then he sits up straighter. To think of another way to get Mum and Dad home.

I’m not giving up, Jay says to them silently.

And even if they can’t hear that, at least he can.

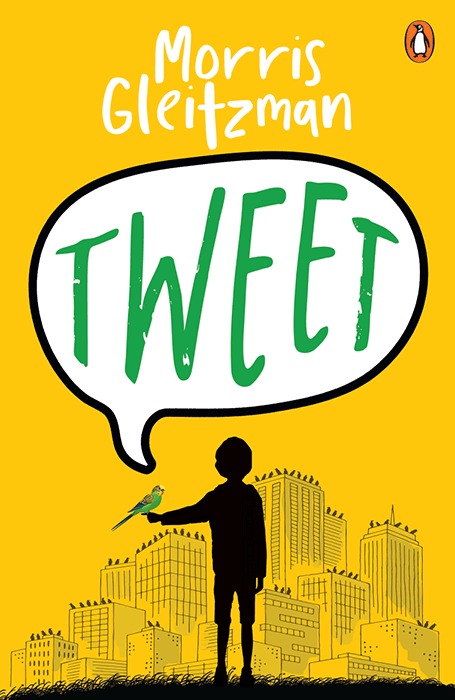

Tweet will be available from April 3 in bookshops and libraries in Australia and New Zealand, and online. Buy it here:

Tweet will be available from April 3 in bookshops and libraries in Australia and New Zealand, and online. Buy it here:

The audio track on this page is an excerpt from the audiobook Tweet, read by Morris Gleitzman. Download as an audio file (from April 3, 2024):

The audio track on this page is an excerpt from the audiobook Tweet, read by Morris Gleitzman. Download as an audio file (from April 3, 2024):

… or just search for Morris Gleitzman on Audible or the iTunes Store.