Listen to Morris read Chapter 1

Chapter 1

Just before the huge storm rolled down the valley, Wilton did.

It wasn’t his fault.

He was on a ledge high over the valley doing his exercises. Or trying to.

‘One push-up,’ Wilton grunted. ‘Two push-ups. Three push-ups.’

It was no good. He wasn’t moving.

Wilton flopped forward onto his tummy.

This is hopeless, he thought. I’ll never lose weight this way.

‘You’ll never lose weight that way,’ said a nearby patch of slime, looking up at Wilton with the know-it-all expression patches of slime are famous for. ‘Push-ups don’t work when you haven’t got any tendrils to push yourself up with.’

‘Thanks for the advice,’ said Wilton.

‘What you need,’ said the patch of slime, ‘is to find the right exercise for your particular physique.’

The slime’s right, thought Wilton. There must be one workout suitable for a very large tube-shaped limbless microbe like me. Something that doesn’t involve push-ups, jogging or cartwheels.

He tried to think of it.

All he could come up with was wriggling.

OK, thought Wilton. If all I can do is wriggle, I’m going to wriggle like I’ve never wriggled before.

He gave it a go.

‘Wow,’ said the patch of slime. ‘Great wriggling.’

Wilton’s wriggles were so powerful and determined that before he knew it he’d done a complete lap of the ledge and was back where he started. Skidding, he saw to his horror, onto the patch of slime.

‘Oof,’ grunted the patch of slime. ‘You haven’t lost any weight so far.’

Before he could apologise, Wilton found himself skidding off the patch of slime, off the entire ledge, and falling, bouncing, rolling down into the valley.

Oh no, he thought. Now I’m in big trouble.

‘Look out,’ he yelled.

Farm-worker microbes flung themselves out of his path, waving their plasma strands in panic. So did livestock. Flocks of viruses bolted. Herds of enzymes cowered together.

Somehow, as Wilton rolled and bounced his way through them, he managed not to crush a single one. The only things he squashed were some of his own front molecules when he came to a sudden stop in a paddock of sludge.

‘Sorry,’ he mumbled to the livestock and the farm workers and his front molecules as he wriggled backwards out of the sludge.

‘I should hope you are,’ said a gruff voice.

Wilton winced.

Glaring up at him, tendrils on hips, was a tiny frowning blob, wrinkled all over with age and indignation.

Oh no, a farmer.

‘What are you doing here?’growled the farmer.

Wilton resisted the temptation to say anything smarty cells like ‘trying to lose weight’.

‘Well?’ demanded the farmer.

‘Um,’ said Wilton. ‘I slipped.’

The ancient farmer scowled. ‘Stop me if there’s anything you don’t understand about the following,’ he said. ‘Our world consists of a valley bottom, where we are now, and the valley slopes up there, where you are meant to stay. Sound familiar?’

Wilton nodded sadly.

‘Good,’ continued the farmer. ‘Because there are very important reasons why you’re not allowed down here, aren’t there?’

‘Yes,’ said Wilton quietly. ‘When I come down here it terrifies the livestock and gives them headaches.’

In the sludge paddocks and along the banks of the sludge river, the viruses and enzymes were still whimpering nervously and some were rubbing their ectoplasms.

‘That’s one reason,’ said the farmer.

‘They’re only frightened of me because they don’t know me,’ said Wilton. ‘Let me stay down here and help out for a while. Do a bit of sludge grooming. Fence a few sludge paddocks. I can make friends down here, I know I can.’

The farmer narrowed his squiz molecules and scratched his grizzled ectoplasm with a work-calloused tendril.

‘Please,’ begged Wilton. ‘I’m lonely up there on the slopes. Let me be a farm worker.’

Wilton’s hope molecules were buzzing. So were his fear molecules. Blurting out his life’s ambition to the gruffest farmer in the valley was one of the scariest things he’d ever done.

The farmer squinted up at him in silence.

Wilton knew this wasn’t a good sign. He hoped the farmer was just pausing to digest his lunch, but when Wilton peeked into the farmer’s protoplasm he couldn’t make out a single virus kebab or enzyme nugget.

‘You’ve already got one big problem, lad,’ growled the farmer at last. ‘Don’t be an idiot as well. You know why we can’t have you down here.’

‘Why?’ asked Wilton, even though he was pretty sure he knew.

‘Because,’ said the farmer wearily, ‘you’re too fat.’

‘That’s right,’ said several muffled voices. ‘Way too fat.’

Indignation molecules vibrated inside Wilton. It was a painful feeling because, as Wilton was the first to admit, he had a lot of indignation molecules. He had a lot of every type of molecule. That was the problem.

‘I’m not fat,’ said Wilton to the farmer. ‘I’m just big.’

‘Way too big,’ said the muffled voices.

‘Fat, big, whatever,’ said the farmer. ‘Modern sludge farming is an exact and demanding science. I can’t have great lumps like you flobbing around the place squashing crops and workers.’

‘I haven’t squashed any workers for ages,’ protested Wilton.

‘You’re doing it now,’ said the farmer.

‘That’s right,’ said the muffled voices.

Wilton felt something tickling under his tummy. He wriggled backwards. A few hundred flattened microbes picked themselves up and tried to push their ectoplasms back into shape. Wilton felt awful. The round ones were sort of oval now, and most of the stick-shaped ones were crinkled.

‘Sorry,’ said Wilton, wishing he had tendrils so he could help straighten them out.

‘We don’t want to hear sorry, fatso,’ said one of the squashed workers. ‘We just want to hear you’re on a diet.’

Wilton felt shame molecules burning inside him.

‘I am on a diet,’ he replied. ‘All I’ve eaten for ages is a bit of water membrane and a few dried viruses with the skin off.’

‘Well,’ grunted the farmer, peering up at Wilton, ‘it’s not working.’

Wilton wanted to let the farmer know that he was also doing an exercise programme. But before he could get the words out, he felt more tickling under his tummy. For a moment he thought more workers were still under there, flapping desperately.

Then he realised it was something else.

The ground was vibrating.

Wilton knew what that meant.

‘A storm’s coming,’ he said urgently to the farmer.

Already Wilton could feel a wet breeze against his skin. The farmer peered down the valley and Wilton saw his ancient tendrils stiffen with alarm.

‘Storm,’ yelled the farmer. ‘Take cover.’

Chaos broke out.

Workers flung themselves in all directions. Livestock stampeded. Enzymes desperately clung to the backs of viruses while the viruses tried to hide behind the enzymes.

Wilton did what he always did when he was caught out in a storm. He curled into a circle, partly to brace himself against the impact of the wind, partly to give some of the farm workers and livestock a place in the middle to shelter.

The storm hit with a roaring squelch.

It was the worst one Wilton could remember. The rain was lashing harder than ever before. It stung Wilton even more than the squashed workers’ unkind comments.

The ground heaved under Wilton’s belly as if the whole valley floor had been infected with a puke fungus.

The howling wind was so savage it tore lumps of sludge from the rippling sludge fields and flung them about like ... Wilton didn’t know what they were like. He’d never seen anything as big as the lumps that were splodging onto the ground all around him.

‘Fat boy,’ yelled the farmer, huddled under an old raincoat made of dead plasma strands and matted whiskers.

Wilton knew the farmer was yelling at him.

‘When this is over,’ continued the farmer, ‘get back up that slope and stay there. If I see you down here again, making the sludge gods angry like this, you’ll be a very sorry microbe.’

Wilton didn’t reply.

He just stayed curled up.

The storm was bad, but it was nothing compared to how miserable he felt inside.

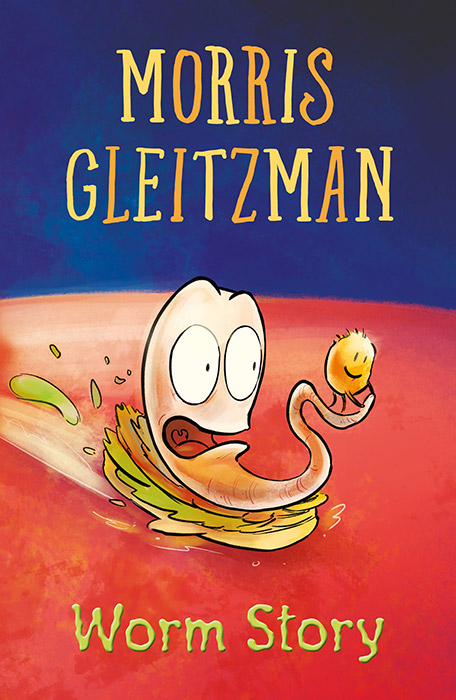

Worm Story is available in bookshops and libraries in Australia and New Zealand, and online:

Worm Story is available in bookshops and libraries in Australia and New Zealand, and online:

The audio track on this page is an excerpt from the Bolinda Audiobook Worm Story, read by Morris Gleitzman.

The audio track on this page is an excerpt from the Bolinda Audiobook Worm Story, read by Morris Gleitzman.

Buy it on CD from Bolinda (or from Amazon in the USA):

… or download as an audio file. Just search for Morris Gleitzman on Audible or the iTunes Store.